From Buttermilk Tower, the view is parched and pure.

The earth curves away from you, toward nothing at all, where everywhere is empty and shopping malls and walls don’t exist.

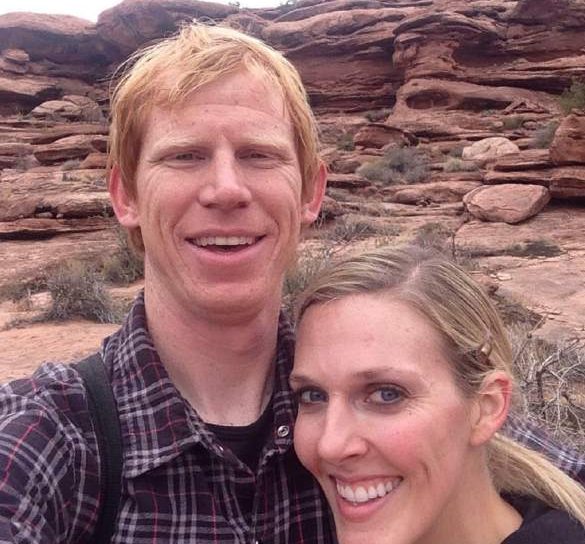

Clayton Hoyt Butler and his wife, Amber Bellows, climbed this tower in Utah. I watched them on my computer screen, my heart thumping. The air whips up there, in my earbuds, as they climbed higher. The two of them stepped out from the metal framework, near the tower’s peak, together.

I’ve never met Clayton or Amber and I never will. I don’t know much more than where my keyboard took me. Clayton and I shared a few, brief messages on Facebook, though, at a time when I was crushed by grief and seeking answers by others who know that weight.

Clayton jumped from the tower, tucked his knees, and disappeared backward toward the golden, rolling hills. Amber followed him. Watching them go down, how easy it had been for them to jump, brought me a small joy. Down on a dirt road, they embraced, their chutes billowing out behind them.

I don’t have much in common with Clayton and Amber besides knowing what love’s like. When I need it though, I’d like to be fearless, or strong enough to see my fear and go on anyway.

Most of my fears are rational but I’m also scared of things against the odds.

In the ocean, an apex predator could take an exploratory bite out of my thigh, the sea foamy red, my body gone icy and white. I can see a man in a white van pulling my daughter into the void where fathers can’t save them. Sadists could roll me tight into a Oriental rug and my would heart burst like a water balloon.

There is a fear I have that makes me scared of being scared too.

I shut down and start back up, no longer the self who’s scared of what’s in front of me. My brain is hijacked and I’m tumbling over earth or attached to a harness above it, unafraid.

One time in Mexico, I heard death’s voice crackle through electric lights. Tour operators had sunk them to the bottom of a crystal pool, down in a hole, deep in the jungle. On and off they went, blackness everywhere, then a brief light, illuminating the pale faces of white tourists staring down at them.

Then black again, all of us alone in the dark, afraid to swim and stop our hearts so far from a hospital.

“Es seguro. Es seguro,” the guide said, only to me, I think.

My wife was there. Our son was so young, beside me. I questioned my Spanish. A fish moved at the bottom of the pool and I jumped in alone, not certain I’d surface. I was so scared and felt so alive.

Somewhere else, years later, my wrist rolled down on the throttle of a motorcycle that weakened my nerve. I broke the ton on an empty highway, so scared but moving faster than my fear, speeding beyond my body.

Scared and alive.

Clayton, I assumed, had been grounded by fear, finally. I thought fear would have shackled him, dragged him back to earth and drilled him down into a cubicle. He would be hemmed in by buildings, saddened but safe near city windows, far from places where you can almost see forever.

Clayton and Amber got married on January 24, 2014 and he lost her about two weeks later, when her parachute failed to open during a BASE jump in Utah’s Zion National Park.

Clayton jumped after her and park officials later dismissed a misdemeanor citation that they filed against him for being there.

I still don’t know what keywords I typed to find his story or why I looked him up on Facebook. Maybe I just felt the universal connection with someone who lost a person they loved.

Clayton found a way to live through it. He didn’t let grief twist him into a broken shape. He was racing cars, jumping out of planes, and smiling. He kept his job: Adventurer.

We started talking, under the guise of me doing a freelance story. I think editors saw my pitch as some grim tour of my mind, though, my pain laid out in a few, hastily written paragraphs that went nowhere. Mostly, when editors and I look at something, we don’t see the same thing.

Trying to move past the death of my closest friend had ground down all the gears I had. I was slipping, sliding backward, certain I had to turn around and drive into the past and cruise around for answers.

The story, if there ever was one, was an excuse to talk to Clayton and go out west and visit him, thinking he had some natural bouyancy, a spirit that could tow me out of my rut. I wanted to see that vista too, something so far from where I stood that it felt like the future, right in front of me.

Maybe I would have stood on a cliff with Clayton, holding a parachute in my hand, trembling from all the reasons I shouldn’t jump. Maybe that thing inside me I don’t understand would throw a switch and my life would gain traction, falling through desert air, moving faster than my grief and guilt.

Clayton told me he only took a few weeks off after Amber died and was planning a 5k race and a BASE jumping show in her honor. I told him I’d get in touch with him after I contacted a magazine. He gave me his phone number. Maybe we’d meet up in Salt Lake City, I wrote.

A few months after our last exchange, Clayton was killed while he was paragliding at Kaena Point on Oahu Island in Hawaii. I found out he died from his Facebook page, where all the tributes and condolences just proved to me that did have some spirit I’d been drawn to.

I felt the loss of a man I’ve never met.

Clayton was so different than me, than all of us who pace along the edge of our fears. He was a living outlier in a commonplace world where people play it safe and mostly die the same way. Death had to chase Clayton through clouds and red valleys, the way a falcon tails a sparrow.

Our conversation was short, but Clayton shared something with me that I knew was worth sharing with anyone who knew him and misses him.

It’s also worth sharing with anyone who wonders how they’ll go on, when someone they loved is gone.

In September, when I was at my lowest point, unable to think about anything but my best friend, I reached out to Clayton.

“How did you deal with the grief?,” I asked him.

This is what he said to me on Sept 2, 2014, a few months before he died.

“I still deal with it. I get real sad when I see or hear things that remind me of her. But I know she wants me to be happy and this earth we call home is spinning and flying through space and it doesn’t slow down or stop cause your sad or had a bad day. The sun rises every morning and you have to be ready for it. It’s ok to grieve but you can’t sit around feeling sorry for yourself.”

Thanks, Clayton.