The Ballad of Jamison Smoothdog began in a South Philly housing project, where a wiry scrapper took that name and cut through the city’s streets like a switchblade with nothing more than a guitar and a voice honed hard by Winston reds.

Stories about the Dog’s days as the alpha male of the South Street music scene have stuck around far longer than his songs. Records were stuffed away in attic corners, melted in his family’s house fire, or lost by people who’d already forgotten them.

On the Web, where a sliver of something can be found on just about anyone, there are no Smoothdog songs to be heard nor vintage performances from the J.C. Dobbs roadhouse to watch.

What remains is a fog of fact and fiction, an urban legend about an enigmatic, fiery frontman who was hard on his guitars, his friends, lovers and lyrics, and on many nights way too hard on his liver.

“He wasn’t great but he was too good to be forgotten,” said Bob Fuentes, who was once Smoothdog’s unofficial manager.

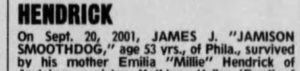

When his life’s coda played out on Sept. 20, 2001, on his liv

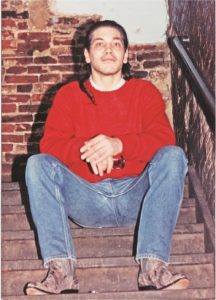

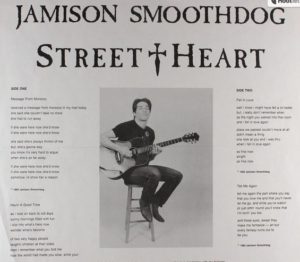

Jamison Smoothdog sitting on the steps of JC Dobbs (behind the stage) 1989.

ing-room couch in Northeast Philly, Jamison Smoothdog was mostly just James J. Hendrick again, a 53-year-old antiques-and-collectibles dealer, a former Marine debilitated by a stroke and type 1 diabetes, still loving music more than anything or anyone besides his beloved mom, Millie.

But Smoothdog himself once said he didn’t “believe a song should ever be finished,” and he has experienced a strange encore online, a steady push for recognition by some who believe he wrote the Southern rock anthem “Can’t You See,” a hit for the Marshall Tucker Band and Waylon Jennings in the 1970s and a tune you might hear on “American Idol” on any given night or onstage at Tootsie’s in Nashville.

Can’t you see, oh, can’t you see

What that woman, Lord, she been doin’ to me

Can’t you see, can’t you see

What that woman, she been doin’ to me

On paper, Smoothdog lost the debate: The U.S. Copyright Office cites Toy Talmadge Caldwell Jr., a founder of the Tucker band and the song’s vocalist, as its author. Not much about Smoothdog’s life is similarly stamped and certified.

Caldwell and Smoothdog can’t sort it out on their own because Toy died in 1993 at age 45, but Dog’s believers hold fast to his story because he wasn’t a man who trifled when it came to music.

“He insisted he did it,” said his nephew Skip Heller, a musician who used to play with his “Uncle Dog” in Philly.

The origins of Smoothdog’s “Can’t You See” story vary, depending on whom you talk to or what you read on songfacts.com, but most other stories about him vary, too. The story usually involves a record label that simply bought the song from him or another one he supposedly walked out on, leaving “Can’t You See” behind because he was ticked off about creative control.

There’s often a woman involved, and one of them, the story goes, went southbound to Georgia, just like in the song, with his words.

Paul Kurrey, 62, a former bassist in Smoothdog’s band, said Jamison almost never did cover songs but once slipped into “Can’t You See” onstage and the rest of the band followed him, confused.

“Afterward, I’d say, ‘Hey man, what’s with the cover song?’ and he’d just say, ‘I wrote it,’ ” Kurrey said recently in an interview at a Starbucks. “And he didn’t want to talk about it. ”

Smoothdog sang the lyrics “Have you heard?” instead of the lines made famous by the Marshall Tucker Band, Kurrey said. The song, Kurrey said, is filled with quintessential Smoothdog: simple, catchy lyrics that are also dark and intense, much like him. The subject of the song, Kurrey pointed out, wants to jump off a mountain because of a woman.

“This is Jamison-level stuff here,” he said, throwing his arms up in frustration.

Others who’ve gone deeper down the rabbit hole believe that the line “Till the train, it run out of track” is a clear reference to the former “End of Track” subway sign on the Broad Street Line at Snyder Avenue. Smoothdog lived near Dickinson and Hicks in South Philly and attended South Philly High School.

None of this is even remotely amusing to Toy Caldwell’s widow, Abbie Caldwell, who has refuted the claims online.

“I do not know what anyone expects me to do. Guess those guys should have read up on copyrighting,” she told the Daily News in an email last week. “I would appreciate not going thru this again. ”

Smoothdog, in a few interviews during his heyday, didn’t mention the song. In those articles he comes across as the intense person everyone says he was.

“Driven people tend to be misunderstood,” he told the Inquirer in 1981. “Other people tend to look on them as selfish and arrogant – that kind of thing. ”

A former engineer with Capricorn Records, the Macon, Ga.-based label that released the song as the first single from the Marshall Tucker Band’s debut album in 1973, didn’t return a request for comment.

Gonna take a freight train

Down at the station, Lord

I don’t care where it goes

Gonna climb a mountain

The highest mountain

Jump off, nobody gonna know

Most people whom the Daily News contacted about Smoothdog started off slowly, as his name fired up the old amps in their heads. They’d say you should really talk to someone else: a guy in Hawaii, a disc jockey in Austin, or somebody who they didn’t realize was dead.

Once they plugged in and started strumming memories, the stories came easily, making them laugh out loud before they’d even finish them. When the conversations ended, many called back or emailed with one more tale about the Dog.

“He had a force field around him. When Jamison entered a room, you knew it,” said veteran Philly rocker Kenn Kweder. “He was dead serious about music. It wasn’t a hobby for him. ”

Kweder said he heard that Smoothdog once killed a cow with a baseball bat because he was starving.

Paul Mick, a friend, fan and “last known manager” of Smoothdog, said rock star Meatloaf once wanted one of Smoothdog’s songs, “The Ballad of Ginny West,” but he “wouldn’t budge. ”

Mick believes that Smoothdog was getting paid to write songs at studios in New York around 1968 or 1969.

“Supposedly, he had Indian blood in him. I don’t know which part,” said Philly drummer George Manney, director of “Meet Me On South Street: The Story of JC Dobbs,” a 50-minute documentary made in 2011.

Smoothdog’s former bandmate Kurrey, who hosts live-music nights and performs at 2nd State Lounge on South Street, recalls Smoothdog smashing a Guild D25 acoustic guitar over their drummer’s head one night on Fitzwater Street, probably prompted by the 1800 Tequila that fueled him, among other things.

“He used LSD as an antihistamine,” Kurrey said, laughing.

Fuentes, the former manager, remembers Jamaican rum as Smoothdog’s drink of choice and it was “all sugar,” he said. “The worst thing to drink if you have diabetes, probably,” he said.

Fuentes recalled a night when the Allman Brothers were playing the Electric Factory and Smoothdog wound up playing a few tunes with Gregg Allman in a trailer outside and Allman dosed Fuentes with LSD.

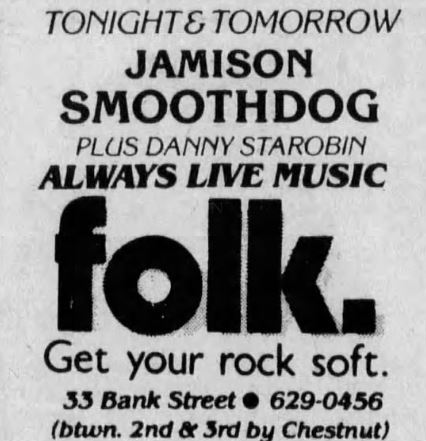

Onstage, Smoothdog played Southern rock before there was Southern rock, Kurrey said, and his voice had hints of Wilson Pickett, Bob Seger, Tom Waits. But no one remembers Smoothdog being influenced by a particular style, and he claimed that all he ever listened to was classical music. Heller said the macho Marine side of his uncle prompted him to use the heaviest guitar strings he could find, and Mick said he’d hit them like a “North Philly boxer. ”

“He broke at least two or three a night,” Kurrey added.

Heller, 49, who lives in Hollywood, Calif., said his uncle was honorably discharged from the Marine Corps because of his diabetes and he bummed around California for a while before returning to Philly. He said his uncle dropped his real name because James Hendrick was too close to Jimi Hendrix, then started playing clubs up and down the East Coast as Jamison Smoothdog.

“He came back from California with two things, two albums: ‘Surrealistic Pillow’ by Jefferson Airplane and ‘Psychotic Reaction’ by the Count Five,” Heller said.

Mick said Smoothdog was a “Jekyll and Hyde” – ornery when he was drinking or not managing his diabetes, but quiet and sensitive when he was sober. That sweetness was mentioned by all his former friends, even though their relationships with him ebbed and flowed.

One remembered Smoothdog saving a stranger slipping into diabetic shock. Another said he gave a box of baseball cards to a sick child. Kurrey said his kids called him Uncle Dog.

“They loved him,” Kurrey said. “He could pick them up and play with them, and turn around and knock a guy out on the street. ”

Heller saw the gentlest side, and growing up he figured he had just about the coolest uncle a kid could wish for.

“He taught me my first chords,” Heller said. “You’re gonna hear all this folklore and legend about him and they’re all gonna be right, but he never forgot anyone’s birthday. ”

I’m gonna buy a ticket, now

As far as I can

Ain’t a-never comin’ back

Ride me a southbound

All the way to Georgia, now

Till the train, it run out of track

Fuentes, 79, bedridden for years in his Collingswood home since suffering a stroke, said there were so many moments when Smoothdog needed one more break to make it big, but fell short.

He said they once drove to New York and faked their way into Fillmore East by slipping inside with a construction crew and bluffing their way into a meeting with famed promoter Bill Graham.

“I said, ‘Jamison, quick, grab a hold of the back of this ladder,’ ” Fuentes recalled.

They played Graham a tape, Fuentes said, and got booked to open for Santana – and then the Fillmore caught on fire.

“He was right on the edge, all the time,” Fuentes said of Smoothdog. “He had good moves and he wrote good tunes. We were friends longer than we were enemies, and that makes me happy. ”

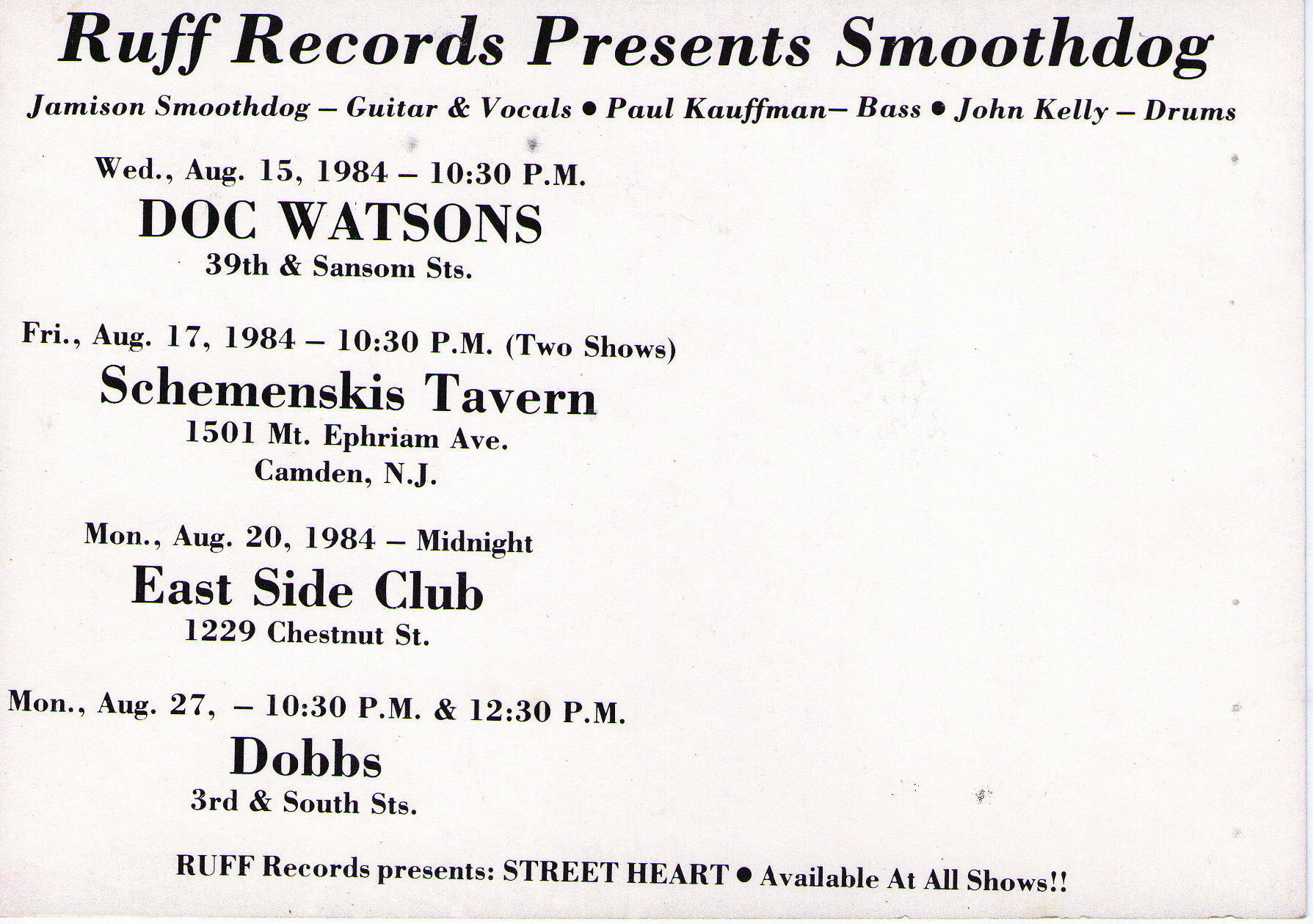

Smoothdog flowed through several combinations of bands in the late ’70s and early ’80s, and did some solo shows, and when he no longer was aiming for stardom he worked at pawnshops and got into antiques and collectibles, eventually opening his store, “Jamison Smoothdog Presents,” on Haddon Avenue in Collingswood while also selling items at stands at local flea markets.

No one ever got the sense that he truly loved the trade, though; it just made him money when music no longer did.

“If the music was doing well, he wasn’t doing antiques,” Kurrey said.

Even if collectibles weren’t a love, customers said Smoothdog had a knack for them, too, and a little air of mystery remained.

“He always had stuff that no one else had,” said Society Hill lawyer Doug Grannan, who went there for Marvel Comics action figures. “He could get whatever you wanted and never gouged you. ”

Smoothdog didn’t talk music much in the store, Grannan recalled.

Toward the end, Kurrey had a falling out with Smoothdog like almost everyone else did. It was over a woman; Kurrey said Smoothdog blew through them “like balloons. ”

“I wish, at the end, that it could have been different for us,” he said.

Smoothdog was hoping to play again, his nephew said. The strength sapped by the stroke was returning, and he wanted to keep telling himself that the song never ends, that he hadn’t reached the end of the track.

“He’d talk about some new musician he met, and that he was hoping to get something going, but I think he knew he was at the end of things,” Heller said. “At one point he said to me, ‘I’m not Smoothdog anymore. I had to let him go.'”