A baby robin died in John Francis’ hands when he was a little boy on Pike Street in the Nicetown section of Philadelphia.

Years later, after two oil tankers collided in the fog beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, he watched the black, toxic goo slowly smother the shore. Not long after that, near his new hometown in California, a man with whom Francis had nothing in common – but whom he respected – drowned.

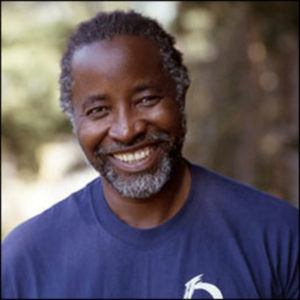

These are John Francis’ three epiphanies, his three major collisions with reality during his 64 years. Each helped transform him from a skinny, self-described “jive-ass” Roman Catholic High grad with no clear direction, to a hippie who even his father thought had lost his mind when he stopped talking or riding in cars, to an author and a Ph.D.

After 17 years of silence, Francis spoke again two decades ago, and now speaks to audiences all over the world about environmental awareness.

“I learned that if something is wrong in your world, you should fix it, or at least try,” he said recently, sitting in a coffee shop in his new hometown of Cape May. “There really is no sense complaining about things. ”

Francis was a leader in the environmental movement before it bloomed.

He founded the nonprofit organization Planetwalk in 1982, has been a goodwill ambassador for the United Nations environmental program, and is developing Planetlines, an environmental-studies curriculum for the National Geographic Society that would help students around the world get out of the classroom and into nature.

His book Planetwalker: 22 Years of Walking, 17 Years of Silence, published last year by National Geographic, has been optioned for a feature film and he already has a local guy in mind to play his role.

“I’m thinking Will Smith,” he said, cracking a big smile.

Francis’ journey back and forth from Philly to California to Cape May has been an especially long one, mostly because he gave up cars and traveled by foot for 22 years after witnessing that disastrous oil spill in January 1971. He walked across the country through the ’70s and ’80s, getting lost, working odd jobs, amassing college degrees and girlfriends, and gaining notoriety as a modern-day Johnny Appleseed who planted ideas by not saying a word.

Francis has walked the length of South America on goodwill missions, through the Amazon, agreeing to hop on a plane when his journey seemed over so he could walk in Antarctica.

Giving up automobiles in the age of the muscle car and talking about environmentalism before it had a clear definition resulted in too many arguments, Francis said, so on his 27th birthday, the soft-spoken hippie stopped talking for one day. He remained almost completely silent for the next 17 years.

“I hadn’t been listening to anyone at all, and I wanted to start, you know, really listening,” he said of his decision to stop talking.

Francis said he’d had a fine upbringing in Nicetown, living with his father – a former line foreman with Philadelphia Electric – his mother and a brother, and vacationing in the summertime in the family’s cottage in Cape May.

He was interested in joining a monastery while at Roman Catholic, but was put off by – of all things – the vow of silence. He managed to avoid the Vietnam War because he was a conscientious objector, and attended LaSalle University briefly before dropping out.

“I wasn’t ready to go to school,” he said.

Francis moved to California on his birthday in 1969 and settled in Point Reyes Station, a small farming community north of San Francisco that became a haven for hippies, he said, and his home for nearly 40 years. He embraced the hippie lifestyle, listening to avant-garde music, eating organic food and ticking off a local sheriff’s deputy, a family man with a white picket fence with whom Francis had a “cat and mouse relationship. ”

That man, Gerald Tanner, drowned in 1971 when his boat capsized in Tomales Bay, Francis said, and it made him realize how fragile the American dream was. He and a girlfriend went for a 20-mile walk to remember the man.

“I realized no one is promised tomorrow,” he said. “No one is promised money. We can only hope for the best. I guess I never stopped walking after that. ”

On the road, Francis’ experiences were “99.9 percent” positive. Even if strangers didn’t understand his silent message, he would find that meals had been paid for him in small towns or would come upon jugs of water left behind on hot roads.

At the University of Montana, he earned a master’s degree in environmental studies and even taught a class without speaking. He earned his doctorate in land resources from the University of Wisconsin and continued walking east until 1990, when he dipped his toes in the Atlantic Ocean at Cape May.

Francis moved here in January and is fixing up his father’s old house with his wife and two young sons. He’s also preparing for his annual 100-mile walk on Earth Day.

Not wanting his vows against cars and speaking to overtake his message, he ended both of them in the ’90s with little fanfare. In 1990, he broke the vow of silence when he said “Thank you for being here” to a crowd who had come to hear him speak in Washington, D.C. A few years later, Francis decided to board a bus while walking on the border of Venezuela and Brazil.

He now drives a Toyota Prius.

“I finally had learned what it meant to communicate,” he said of his decision to speak again. “And I had something to say. ”

Watching the environmental movement spread across the country over the decades and evolve into the modern-day “green” phenomenon has been satisfying, Francis said, but his concerns for the planet still run deeper than switching to more-efficient lightbulbs or hard science discussed by fellow Ph.D.s in his field.

“People are part of the environment,” he said, leaning forward in his chair. “The way we treat each other is part of the overall environment. We have to learn how to treat one another better for this to work. ”

For more information about John Francis, see www.planetwalk.org.