SHAMOKIN, Pa. — A mountain made of things nobody wanted rose in the gloom beyond the end zone during football practice on a dreary afternoon.

Players stood soaked in soggy cleats at midfield, that heap of worthless rock and anthracite rubble framed perfectly between the goal posts. The Shamokin Area High School Indians were coming off a 48-0 loss to Southern Columbia three days earlier, and downpours made this mid-September Monday all the more miserable.

Locals call that distant peak the Glen Burn, after the colliery that cut black diamonds from the hills back when coal was king here, when the boys’ great-grandfathers knew they’d be trading graduation caps for hardhats and going down into the mines.

Shamokin’s coach, 29-year-old Henry Hynoski, was only about two months into the job, but already a coal region legend, and not just for the Super Bowl he won with the New York Giants in 2012. Hynoski knew his Indians were beaten up, their ankles tender and muscles sore. He let practice run long, though, hoping rain could wash away not only that loss, but perhaps a larger sense of failure that pervades among the people in these hills. The team went 2-18 over the last two seasons, and Shamokin, a Northumberland County city of 7,061 people that lost more than half its population over the last half-century, is on Pennsylvania’s version of municipal life support.

“I want them to hate losing as much as they love winning,” Hynoski said of the team. “They are used to losing.”

Some players hurt somewhere deeper, like the stout running back who yanked off his helmet and walked off halfway through practice, muttering resignations to himself.

Raindrops streamed down the kid’s face. Steam curled out from his mop of hair.

Hynoski followed him into the locker room.

“I will change the culture around here,” he said, loud enough for everyone to hear.

Hynoski was born and raised in the village of Elysburg, 16 miles to the north, home of Knoebels Amusement Park and not much else but corn. Like many in coal country, his grandparents emigrated from Poland. His father, Henry Sr., was his idol, playing football for Mount Carmel High School, then Temple University, and, ultimately, for the Cleveland Browns.

The elder Hynoski, a running back, kept Cleveland’s iconic orange helmet on display in the home to inspire his son.

It worked.

In high school at Southern Columbia, Hynoski Jr. won four state titles, rushing for 7,165 yards and 113 touchdowns, a back with cannonball calves who dragged defenders over the goal line or simply bowled them over. The New York Times once wrote about his many nicknames, including Hank the Tank, the Polish Hammer, and Hynoceros, forgetting about Rhino and Hyno.

“Best blocking back I’ve ever seen,” said Shamokin school board member Bob Getchey.

Hynoski left the University of Pittsburgh early for the NFL, valued by scouts for his 6-foot-1, 266-pound frame, his love of contact at the selfless position of fullback. He blocked. Other players got the glory.

“It’s the best position,” he said.

Around Elysburg, locals put his name on marquees and named burgers after him when the Giants signed him as an undrafted free agent in 2011. Hynoski played four seasons with the team and made a crucial fumble recovery in Super Bowl XLVI, his rookie year, that helped secure the win for the underdogs over the New England Patriots.

Hynoski is too modest to talk about the money he made in the NFL, but online estimates say it eclipsed seven figures during his career. A fan favorite who battled injuries, Hynoski was released before the 2015 season, and neither New York or even East Rutherford, where the Giants play, would ever be his home.

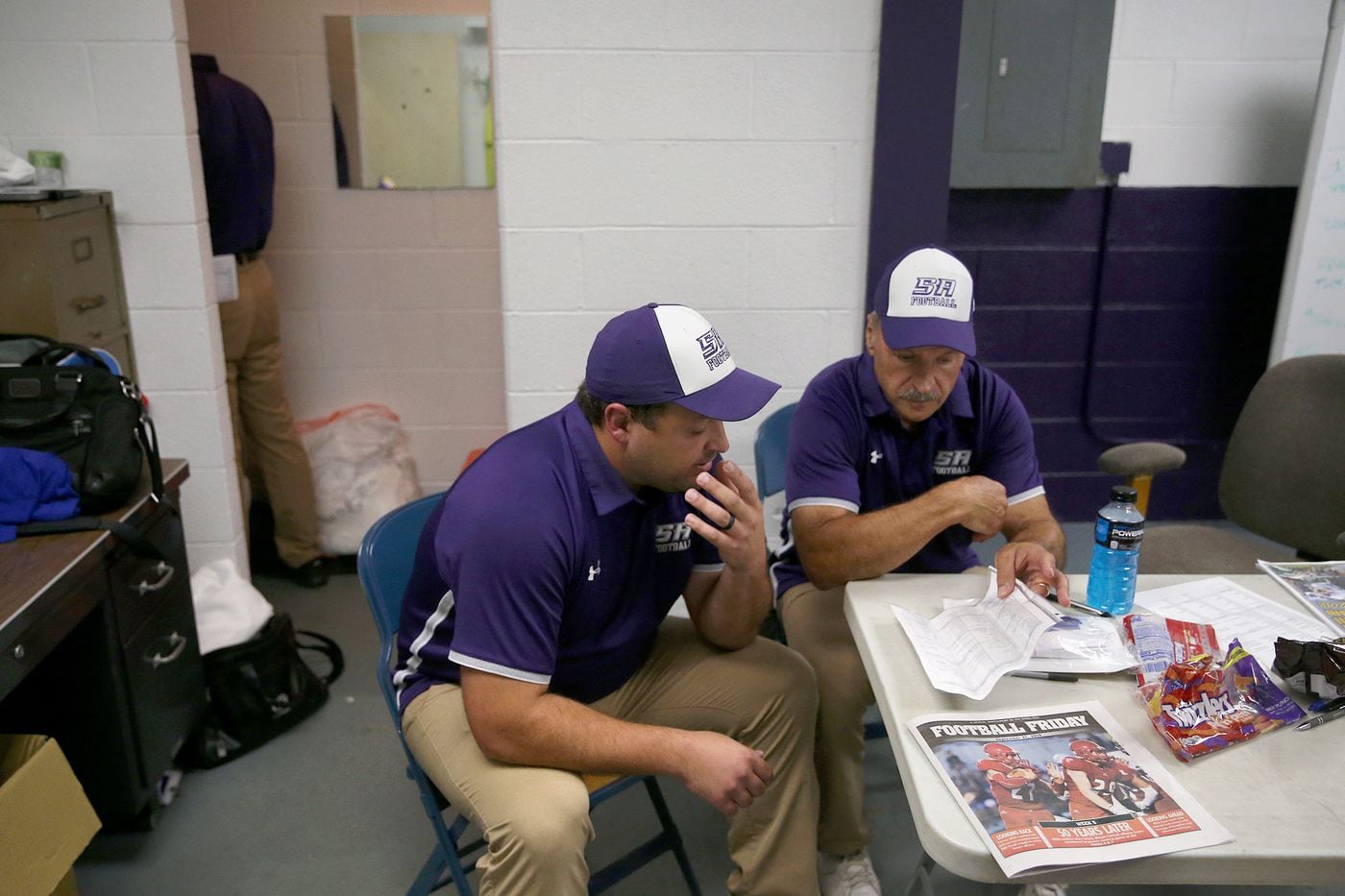

“I always knew he’d come back,” said his father, now an assistant coach at Shamokin. “He’s good for this area.”

Getchey takes the credit for courting Hynoski, who completed a master’s degree in business communications and information technology at Bloomsburg University after football.

“I called my cousin one night — God bless him, he’s deceased — and I said, ‘I think I’m going to call Henry Hynoski. He’s going to be graduating soon, and I wonder if he’s interested in coming back to the coal region,'” Getchey said. “We needed this. The kids would play for him. Biggest no-brainer there was.”

Hynoski lives in Elysburg with his wife, Laura, and their son, Hudson, 1. He’s the dean of students at the high school, in his players’ eyes and ears even more. A drawing of Hynoski hurdling former Dallas Cowboys cornerback Terrence Newman sits in his bare office.

“There’s a little pressure to it,” he said of coaching, speaking before that rainy practice began. “Everybody kind of expects miracles right at the start.”

Downtown, in the billiards halls and greasy spoons where miners used to wash the dust down, old-timers still gather to talk, or mostly yell, about the glory days of football and coal and everything else.

“We were just talking about the Indians before you came in,” said Joe Bordell, a retired teacher sitting at the counter at a Market Street pool hall.

The team, Bordell pointed out, was already 2-2 after just four weeks, with a big homecoming game that Friday night. Was Hynoski dragging the hardened closer to hope?

“No way they’re beating Lewisburg, ” Bordell said.

“Ah, hell, they’re going to win,” Dan Derck, 64, shot back.

Shamokin’s famous son, Stanislaus Coveleski, also tied hope to sports. Stan Coveleski quit school at 12 to work in the mines. Baseball got him out and into the Hall of Fame, a spitballer with a .602 winning percentage who played in the majors from 1912 to 1928.

Nowadays, there’s no mining to escape from.

“This city is just a shell of what it once was,” Bordell said. “First off, there’s no jobs. Zero. None.”

Top employers in Northumberland County, according to Pennsylvania’s Department of Labor and Industry, include school districts, health networks, food distributors, and government. Only five of the top 50 employers in the county had a Shamokin address, a spokesman said.

A century ago, during the height of coal’s reign in the state, 330,000 miners produced 277 million tons of coal worth $705 million. Last year, an anthracite coal executive said approximately 1,000 worked in the industry now.

Not coincidentally, Shamokin’s population peaked around a century ago, at 21,204. Today, it is one of 17 municipalities under Pennsylvania Act 47, a program administered by the state Department of Community and Economic Development to keep cities “experiencing severe financial distress” afloat.

The median household income of $30,925 is 43 percent lower than the state average.

President Trump campaigned on a promise to bring coal back, and it resonated in Northumberland County, where he won nearly 70 percent of the vote. Banners for Trump and others that read “Wealth through Coal” and “Make Shamokin Better than ever, together” hang outside one home that overlooks the creek in this hilly city.

A few blocks away, Robin Pees sat on the front porch of a rowhouse festooned with Trump lawn signs, smoking cigarettes and experiencing what psychologists call cognitive dissonance.

“You don’t feel Trump here in Shamokin at all,” she said. “You don’t feel Trump and coal at all.”

Coal and politics fade, for a few hours at least, on Friday nights at Kemp Memorial Stadium, wedged between Little Mountain and Big Mountain with the manmade Glen Burn in the distance.

A thousand fans spread across the home bleachers, all in purple. Some students wore Christmas attire — “because it’s fun” —and potential homecoming queens were towed around the track on a utility trailer.

The snack stand, like many in coal country, served pierogies.

“You can’t beat Friday night football in the coal region,” said former player Rob Schiccatano.

Brycen James, the running back who had walked off the practice field days earlier, seemed to take on Lewisburg and the doubters that remained among the home crowd by himself. He struck early on defense, with a 54-yard interception returned for a touchdown, and later recovered a fumble.

On offense, Hynoski fed James the ball 19 times for 98 yards. Some runs ended in losses, with James shifting his hips and reversing direction, fighting off gangs of tacklers.

“He don’t go down easy,” Bordell said.

James broke off a 55-yard touchdown run and plowed into the end zone from the 1-yard line for another one, too.

Shamokin won by 27-7. Everyone but Hynoski, it seemed, was shocked.

“We like proving doubters wrong,” he said.

When James, 16, yanked off his helmet after the game and fans gathered around him, a smile spread across his sweaty face.

“It was frustration,” he said of Monday’s practice. “I just want to win.”

Hynoski’s wife, watching her husband and James do interviews together after the game, said he “loves that kid.”

“Sometimes they get overemotional, but that’s what it takes sometimes,” Hynoski said. “You want guys like that, with fire.”

No one mines the Glen Burn these days, out beyond the goal posts. That dark throne has long been empty.

A fire smolders deep inside it, though. Locals say that when it rains, you can sometimes see the steam rising from its depths.