While looking for guidance from his literary hero, Norman Maclean, Jason Nark discovered Pete Dexter—whom he found just as intriguing. He tracked Dexter down to talk about the writer they both loved.

By Jason Nark

Originally published on Narratively.com

Sometimes, when red-winged blackbirds sing in the reeds or clouds turn electric pink in the day’s afterglow, nature will untie my mind and I’ll forget to keep fishing. My thoughts will drift over the water while I take a beat from my favorite pastime and settle on people I’ve loved and lost, on writing or, often, on the late author Norman Maclean.

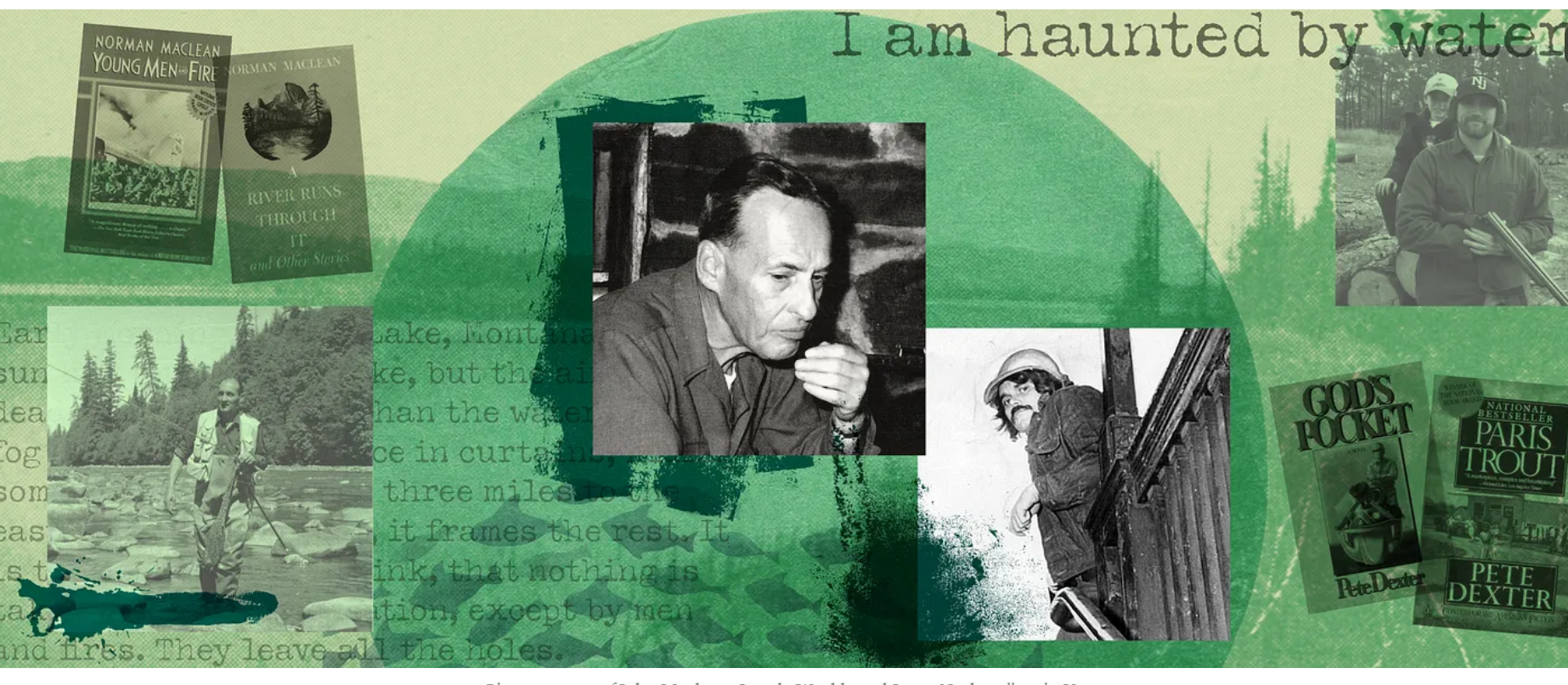

A literature professor at the University of Chicago for nearly a half-century, Norman Maclean equated fishing with religion, his Montana river valleys with cathedrals. His 1976 semi-autobiographical novella, A River Runs Through It, the book that made Maclean a household name, is a lyrical meditation on the high art of fly-fishing. It’s scripture for some, myself included.

I first read A River Runs Through It in graduate school for an influential nature writing class, and it’s stuck with me ever since, a steady guide through the changing seasons of my life. Sometime around 2012, while writing a long essay about fatherhood and the outdoors for a short-lived weekend publication called SportsWeek from the Philadelphia Daily News, I was looking to Maclean, once again, for guidance and stumbled upon a 1981 profile of him in Esquire called “The Old Man and the River.” The piece delves into Maclean’s obsessive process, his writing routines and the fact that he became an author later in life. I checked the byline: It was written by Pete Dexter.

When I found the Esquire profile, I was seeking inspiration from Maclean for my essay, not from the profile’s author. Magazine profiles tend to be formulaic, I thought. You learn what day of the week it is, what the weather’s doing, and then the author describes her breakfast order as she waits for the reluctant celebrity she’s profiling to show up in a trendy cafe. Soon you learn what the celebrity eats too. I guess it’s better than a phone interview? But Dexter’s Esquire piece created a sense of place I hadn’t seen, something that felt new and timeless at once.

“Early morning, Seeley Lake, Montana. The sun has touched the lake, but the air is dead-still and cooler than the water, and the fog comes off the surface in curtains, hiding some of the Swan Range three miles to the east. And in doing that, it frames the rest. It is the design here, I think, that nothing is taken without compensation, except by men and fires. They leave all the holes.”

When I finished the second paragraph, I stopped and reread it all from the beginning, thinking, “This is just as good as Maclean.” I later learned that this was Pete Dexter’s first national magazine profile and his editor, when I spoke to her recently, told me she might have moved a few commas around, but nothing else.

“On the lake, a cutthroat trout breaks the surface; pieces of it follow him into the air. He breaks it again, falling back. The water mends itself in circles; the circles disappear. You could never say exactly where, but that’s how things mend; it’s how you get old, too. Not that they are necessarily different things. The place is quiet again. The sun has touched the lake, but the lake still belongs to the night. To the night and to the old man.”

***

Dexter is a former Philadelphia Daily News columnist who later turned to fiction and won a National Book Award for his novel Paris Trout. I worked at the Daily News too, decades later. Like most Philly journalists, I knew about the infamous night Dexter was nearly killed over a column in which he described an overdose victim as “stoned all the time.” I’d heard older editors speak of him in reverential tones and saw his photo on the wall of past and current journalists, but I’d never actually read any of Dexter’s work until I stumbled upon the profile of Maclean while in my mid-30s. Maclean and Dexter have been entwined for me ever since, whether I’m paddling down some murky creek in search of fish or staring at a blinking cursor on my laptop.

Dexter, from what I could tell, was last interviewed in 2015 when he was the keynote speaker at In the Footsteps of Norman Maclean, a biennial literary festival in Seeley Lake, Montana. He’s 80 now and lives in Vermillion, South Dakota, where he teaches creative writing at the University of South Dakota. It’s been about 15 years since he published his last novel, Spooner. Dexter’s far too good a writer, I thought, to be forgotten.

Earlier this year, when Narratively put out a call for pitches on the art of narrative storytelling, with profiling your “narrative nonfiction hero” as one example of what that might look like, I immediately thought of Dexter’s profile of Maclean and decided to track him down. A writer interviewing one of his favorite writers about interviewing one of their shared favorite writers. It would scratch an itch I’ve had for over a decade to pick Dexter’s brain, and I’d also be doing a service to past and present colleagues by interviewing him. Most thought he still lived on an island in the Puget Sound, north of Seattle, where he’d last done interviews. Others assumed the worst.

“He didn’t die, did he?” a Philly writer asked me in April when she helped track down a former editor of Dexter’s.

***

I figured I’d fly to Sioux Falls, rent a car and drive south to Vermillion. I imagined seeing some bison out there and browsing through old bookstores with Dexter, maybe falling asleep on a mountain of newspapers after reading some of the trilogy he’s still working on but won’t tell me about. Dexter didn’t think we needed a whole weekend together, but I made a second offer to fly out just for a long lunch.

He wanted some time to mull it over.

Dexter did once tell a Missoula newspaper that “so many writers are people I don’t want to spend time with.” Then he added: “To put it kindly, most of them are strange and have been through some stuff.” So I knew that it was probably a longshot.

Following the Esquire discovery, I went down a deep Dexter rabbit hole. The Philadelphia Daily News and Inquirer had traded its beloved ivory headquarters for office space in a former department store by then. There were no more dusty archives filled with fading newspaper clippings to stain my fingers, so I dug into Dexter’s clips on today’s equivalent, Newspapers.com, instead. I learned that he was a keen observer of violence, writing about slit throats and stabbings, biker gangs, and a Philly mob boss who’d gotten blown up on his porch. He wrote about aimless teens sniffing paint remover or throwing rocks at each other during neighborhood beefs. He could also be funny as hell.

“He is sometimes the very best there is,” a Philadelphia Magazine writer said of Dexter in a 1979 profile.

Sometimes Dexter’s columns transcended what I thought journalism could be. “Hawk Shadows,” the first column in the 2007 compilation Paper Trails: True Stories of Confusion, Mindless Violence, and Forbidden Desires, a Surprising Number of Which Are Not About Marriage, is my favorite. I think most newspaper editors would scratch their heads if it were filed today. “Hawk Shadows,” which appeared in the Daily News in 1979, is essentially a short story, as fine an example of nature writing as anything Aldo Leopold, Mary Oliver or even Maclean himself wrote.

“The hawk was waiting in a high limb of one of the tallest pine trees in the woods across the road. The man had seen her hunt from there before. She was brown in the face and wings and a redder color across her chest. When she left the limb, her wings would pump the air slowly, and it was the nature of her power that you could see the effect of each of the strokes on her flight.”

Dexter’s dry humor is there, too, in the back-and-forth between a husband and wife worried whether hawks and other predators would snatch up kittens in their yard. The final paragraphs, though, where Dexter hints at past traumas haunting the present, where he flexes the nature of his power with words, make you want to give up writing completely.

“The man walked over to the cat. She searched his face then came up on her hind legs, asking for her kitten back. He held out his hands to show her he didn’t have it, then started for the house to get her some milk.

As he moved, his shadow crossed the cat and she cringed, and this is what he would lie awake thinking about that night and the next.

The man had lost things that had mattered before and he knew what it was to cringe at sudden shadows, the ones that just drop on you out of the sky.”

***

In his 1995 novel The Paperboy, Dexter wrote, “No one interested in how newspaper reporters find their stories should imagine that the compass needle is reset each time out. What they find attractive doesn’t change, only where they find it.” I get that, implicitly. Dexter was always in search of bruised lives, dramas great and small, and those everyday, imperfect moments. Sometimes Dexter’s needle pointed to his backyard, like in “Hawk Shadows,” other times to a Philly street corner, like when he wrote a eulogy-of-sorts about his friend “Pally” being randomly beaten to death after leaving a bar one night in 1979. In the Christmas of 1980, the needle pointed him to the Maclean brothers in a copy of A River Runs Through It, and he went looking for its author.

“It is the truest story I ever read; it might be the best written. And to this day it won’t leave me alone,” he wrote in Esquire.

Dexter, in the Maclean profile, wrote that A River Runs Through It is about “not understanding what you love, about not being able to help.” The story focuses on Maclean and his younger brother, Paul, a preternatural fisherman and newspaper reporter who often found trouble in Montana where they grew up in the 1920s. Maclean struggles to keep Paul on the side of the angels, or to even understand his motivations, and often they simply fish when there’s nothing left to say. My own copy’s grown dog-eared in these passages where Maclean feels helpless to understand his brother.

“It is those we live with and love and should know who elude us,” Norman’s father tells him toward the end. It gets me every time.

***

Even though Dexter told me the first time we spoke on the phone never to accept a phone interview over the real thing, he called back a few weeks later and told me he couldn’t do “things like this” anymore, meaning in-person interviews, since his wife, Dian, died in 2018. He seemed disappointed in himself for saying “no” and apologized, and I’m not the kind of reporter who would probe that wound with questions, so that was that. Dexter and I aimed for a phone interview instead, on Easter weekend, when I’d be in Florida on vacation with my family. I eventually called him from my daughter’s car, while wearing my bathing suit, as my dad and two sons fished from a bridge in Cocoa Beach. Not exactly the bison I’d been envisioning, but at least I wouldn’t have to describe what Dexter ordered for lunch.

When I first saw Dexter’s byline in Esquire all those years ago, I wondered what drew a city columnist from Philly to seek out a nature writer in Seeley Lake, two places that seemed as different as a punch in the nose and a pimple. Dexter, from what I’d read, wasn’t exactly an outdoorsman in those days.

“Are you asking if I was interested in fishing?” he’d said matter-of-factly when I finally got to ask him about it. No,” he replied bluntly.

During our call, Dexter told me he’d come to Maclean in his mid-30s (ahem) when he was branching out into magazine writing and thinking more about fiction. He would publish his first novel, God’s Pocket, two years later. In the Esquire profile, Dexter mentions that his brother, Tom, gave him a copy of River for Christmas. Tom was a student of Maclean’s at the University of Chicago. Dexter told me Maclean’s story “sort of staggered” him, and he wrote in the profile that its 104 pages “filled holes inside me that had been so long in the making that I’d stopped noticing they were there.”

Maclean didn’t sit down at the typewriter to start the first of his two books until after he was 70 and retired from teaching. Dexter told me he went to Montana to interview Maclean and write the profile mostly out of plain old curiosity, the driver for most reporters, but he was particularly fascinated that Maclean had committed to writing and publishing so late in life.

“I always thought I started late, but certainly not as late as he did,” Dexter told me. “I was amazed that suddenly this guy had picked up his typewriter and put this together.”

Maclean knew he wasn’t going to be prolific, given his late age when he started, and told Dexter, “All I could hope to do was write a few things well.” Which he certainly did. His second book, Young Men and Fire, is just as important to me, a how-to for tackling a large creative nonfiction project.

When I’d asked Dexter what he learned about writing from his week in Montana, he settled on Maclean’s attention to detail, his knowledge of every wildflower or tree in his stretch of the world. “The details,” he said. “That’s where the truth really is, and I don’t mean truth with a capital T.”

Dexter was also struck by how much Maclean cared about word placement, spending ages on single paragraphs. Maclean had told Dexter as they drove along, “I assemble pieces of ordinary speech. Every little thing counts. You take the way it comes to you first, with adjectives and adverbs, and cut out all the crap. You use an adjective, it better be a $64 adjective. Turn off the faucet and let them come out a drop at a time.”

According to Dexter, a writer’s ears are as important as any other tool they have. “That’s how I came to my writing,” he said, “by listening to the strength of a sentence as I’m laying it out.” He can hear the wrong word like a broken guitar string, he explained, or if words are landing on the right beat in a sentence when he reads them aloud.

“Without an ear, you’re not gonna get far,” he told me. “That’s what people are talking about when they talk about talent. A lot of it means having an ear.”

Dexter, in the profile, wrote that every sentence and paragraph of Maclean’s writing depends on the previous one to carry meaning. It’s like building a house. I thought of River’s final paragraphs, how its last sentence — “I am haunted by waters” — is so heavily quoted when the earlier words build to it. It’s not a kicker most reporters would write.

“Now nearly all those I loved and did not understand when I was young are dead, but I still reach out to them.

“Of course, now I am too old to be much of a fisherman, and now of course I usually fish the big waters alone, although some friends think I shouldn’t. Like many fly fishermen in western Montana, where the summer days are almost Arctic in length, I often do not start fishing until the cool of the evening. Then in the Arctic half-light of the canyon, all existence fades to a being with my soul and memories and the sounds of the Big Blackfoot River and a four-count rhythm and the hope that a fish will rise.

“Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it. The river was cut by the world’s great flood and runs over rocks from the basement of time. On some of the rocks are timeless raindrops. Under the rocks are the words, and some of the words are theirs.

I am haunted by waters.”

Novelist Betsy Carter was Dexter’s editor for the Esquire piece. When we spoke over the phone recently, she told me she was surprised that Dexter, whose voice was so “distinct and original,” revered another author so much. It makes more sense, today, she said, given Dexter’s trajectory after the profile ran.

“Maclean was something he could aspire to,” Carter said, “because he was right on the verge of that life.”

When Maclean died in 1990, Dexter, in his Sacramento Bee column, wrote that America had lost its best writer, and that A River Runs Through It was the “most beautiful and profound literature that has been written in this country since the death of Robert Frost.”

When we spoke, Dexter said A River Runs Through It “satisfies the ear” still to this day, always, but he doesn’t worship it the same way he did in 1981. He attributes that to “growing up.” Dexter, today at 80, wonders whether the story needed to end with “I am haunted by waters,” or whether what he wrote was instead one sentence too many.

“I think it belonged and he wrote this beautiful thing and I’m not gonna take it apart, but that long sentence before that line, it’s sort of a summing up of life. There’s a lot of stuff in there and at the end of it, where he says ‘And a river runs through it,’ that to me was the sentence to end it on,” he said. “‘I am haunted by waters’: That surprised me and made me envious when I first read it. I still think it belongs and the story would suffer without it. I just think it’s in the wrong place.”

Dexter recalls ruffling feathers when he brought this up at the festival in Seeley Lake in 2015, but the organizer and Norman’s son, John, also a journalist and author, had nothing but praise for him when I spoke to him recently. John Maclean said Dexter was invited to speak specifically because his profile wasn’t “hagiography.”

Maclean himself, on the other hand, didn’t like the profile, John shared.

Dexter had heard that, too — he told me the elder Maclean was annoyed that the word “old” popped up so much in the profile, particularly in the headline. Considering he took Dexter hiking up and down mountains all week, wearing him out, Maclean had a point.

“He [also] didn’t like that I’d quoted him saying ‘hell’ or ‘damn’,” Dexter said.

***

Months after the Maclean profile ran, Dexter went to a bar in Philly’s Grays Ferry neighborhood to talk to folks angry about the column he’d written about the overdose victim. The crowd took their grief and anger out on Dexter instead, shattering his teeth and breaking many of his bones. He was left with nerve damage, a brain bleed and 90 stitches. He began writing God’s Pocket shortly after and his career took a hard turn.

“He is a powerful writer whose skills may outgrow journalism,” a book reviewer wrote about Dexter in 1984 after the novel debuted.

Maclean wrote Dexter a long letter when he learned about the beating. His brother, Paul, had been beaten to death in Chicago, his body found in an alley one morning in 1938. Paul, the character in A River Runs Through It, died violently too.

“Here was a letter that couldn’t have been kinder. It was like it was from a relative,” Dexter said. “He didn’t end up saying anything about his brother, but I took that from the tone of it. He said he sat there weeping from hearing the news, and it wasn’t said in a way that was false or anything like that.”

When I asked Dexter if he could read me the letter, he was silent for a moment.

“I lost it, of course,” he said, “along with everything else.”

There was silence again, after “everything else,” then Dexter said he was all talked out. I told him I understood, and we said our goodbyes. On my long drive home from Florida back to the Northeast, I wondered what a different writer might have asked Dexter to break the moment, to put the pain into words.

Had I had the chance to visit Dexter in South Dakota, I could have observed the details a phone call wouldn’t reveal and tried to write something sublime, like Maclean, or stark and funny, like Dexter. But Dexter told me during our call that he still regrets the time he wrote a column in the style of Hemingway; that emulating another writer is a “path to nowhere,” and I know it’s true, because I’ve tried it a few times myself with little success.

Everyone’s inspired by someone. Maclean told Dexter he was indebted to Frost. Dexter said he once studied a Maclean paragraph for “four hours.” We anguish over the sound of our words, and wonder if there’s one higher note to reach for. When I doubt myself as a writer, or question where my compass leads me in journalism, I think of Maclean and Dexter digging into the profound and the profane, and I don’t mind trying to keep pace in their long shadows.