EACH NEW candle that flickered on a cake meant another year for Marcus, one more improbable birthday, another small victory in a long battle against a lone bullet.

His latest cake was presented Sunday night, July 21, inside a dining hall at St. Joe’s Prep, his alma mater in North Philly. Embedded in the icing was a picture of a red Lamborghini, the car he swore he’d own after becoming a brain surgeon.

Marcus, Happy 40th Birthday was written across it.

He grew up a block away, at 18th and Thompson streets, and he was shot nearby, at 18th and Ingersoll, two months before graduation in 1991.

In this small world of concrete, asphalt and bricks between his house and the imposing Church of the Gesu, Marcus Smith rose up in the late ’80s and early ’90s like some rare and exotic flower amid the dandelions and vines that grow in the cracked sidewalks and crawl up crumbling rowhouses.

He was, according to family and friends, a brilliant, witty and good-looking teen untouched by neighborhood beefs or the crack-cocaine epidemic thriving all around him.

“A lot of people around here put so much hope into Marcus,” said Ed Beckett, a former teacher of religion at St. Joe’s who was tight with Smith and his family.

Smith knew the way out of the maze, Beckett said, and it led through “The Prep,” where he had a scholarship, the church, the youth leagues and all the mentors who saw his promise.

His short-statured but strong-willed mother, Dee Pinkney, and her close-knit family helped guide Smith, and he had an ambition to live large. He vowed to return after medical school, to prove it was possible, to show North Philly kids there was nothing wrong with being smart.

“Marcus was the real deal,” Beckett said. “He would have made it.”

Since the day Smith was shot, more than 6,000 people have been killed by firearms in Philadelphia, lives turned off like light switches, or slowly dimmed to darkness in hospital beds.

Thousands more in the city have been shot and survived, some fortunate to live only with scars – others, like Smith, in wheelchairs.

As if to underscore that gun violence in the United States is an epidemic, the grim statistics are kept by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Those numbers show that 526,580 people suffered violence-related nonfatal firearms injuries in the U.S. between 2001 and 2011.

The bullet that hit Smith damaged the only weapon he’d ever needed: his brain.

Shooter was 16

On April 10, 1991, Smith and a group of friends collided in North Philly with a teenager who was on a different path, a 16-year-old with a gun, who popped it off at no one in particular, over some perceived problem with a girl.

Smith was 17, waiting to go into a Catholic Youth Organization meeting at the time. He rarely left North Philly afterward.

The bullet hit the left side of his neck, cut through cerebral arteries and splintered his jawbone before exiting the other side. His heart pumped most of his blood across the sidewalk, then it stopped beating altogether, starving his brain of oxygen. He spent weeks in a coma at Hahnemann University Hospital.

Months after the shooting, Pinkney accepted her son’s diploma at the St. Joe’s Prep graduation. Smith’s eyeglasses sat on an empty seat during the ceremony.

“There wasn’t a dry eye,” said his classmate Kevin Currie.

There was talk of revenge after Smith was shot, but Pinkney, pregnant with another son, shot it down. She said she didn’t want another mother to end up in the hospital. Smith never knew the name of the kid who shot him, and it wasn’t published because he was a juvenile.

The teen pleaded guilty and was sentenced to three years in a youth program. According to Smith’s friends, the teen was killed later during a gunfight in Philadelphia, although no one was sure whether he was struck by a bullet or wrecked his car avoiding one.

” ‘Live by the sword . . . ,’ you know what they say,” said Smith’s friend Arthur Stewart.

Rose Cheney, director of the Firearm and Injury Center at Penn (FICAP), said gunshots even affect those who aren’t hit, creating a toxic cloud of stress over a neighborhood.

“There’s research that shows that kids who are exposed to gunshots in their neighborhood are more likely to be carrying guns,” she said.

Smith and the church stopped the violence from taking root, friends said, but they struggled after he was shot.

“We all could have been that kid with the gun,” Stewart said, his gravelly voice choking up as he talked about growing up with Smith. “But we had each other. Marcus kept us all together. I will never have a friend like that again.”

Smith spent months at Moss Rehabilitation, later moving to a wheelchair-accessible private residence on North Camac Street for which St. Joe’s Prep helped to pay. A painting of Jesus’ open hands hung above his bed in his first-floor bedroom.

Pinkney looked to North Philly churches for strength, taking her son to Church of the Gesu and, later, to St. Malachy.

“That man over there is going to be 40 years old next month,” Pinkney said in the bedroom in June. “Marcus, how old are you going to be?”

Smith couldn’t communicate verbally. He just continued to stare at his mother, smiling.

“I try to keep him as comfortable as possible,” said Pinkney, a former nurse.

According to FICAP, most gunshot victims in the United States do not have health insurance, and U.S. taxpayers wind up paying for half the costs. A 2005 study of hospital charges in Pennsylvania found that the average hospitalization for a firearm injury was $30,814.

Pinkney estimated the annual cost for Smith at more than $100,000, having had to “fight for everything, even the feeding tube,” including hospitalizations for infections, blood clots and pneumonia over the last 22 years.

“We almost lost him a few times,” she said, her hand on his knee.

She described him as happy at home, although his aide, a burly, soft-spoken man who wanted to be identified only as Gene, revealed an inner life, the losses his mother didn’t like to think about.

“Out of nowhere, and it’s not often, but certain music upsets him. It’s usually music from the ’80s,” Gene said in Smith’s bedroom. “It could be certain groups, and he’ll hear it and all of a sudden you’ll see tears coming out of his eyes. I think it takes him back to when he was young.”

‘The brightest kid’

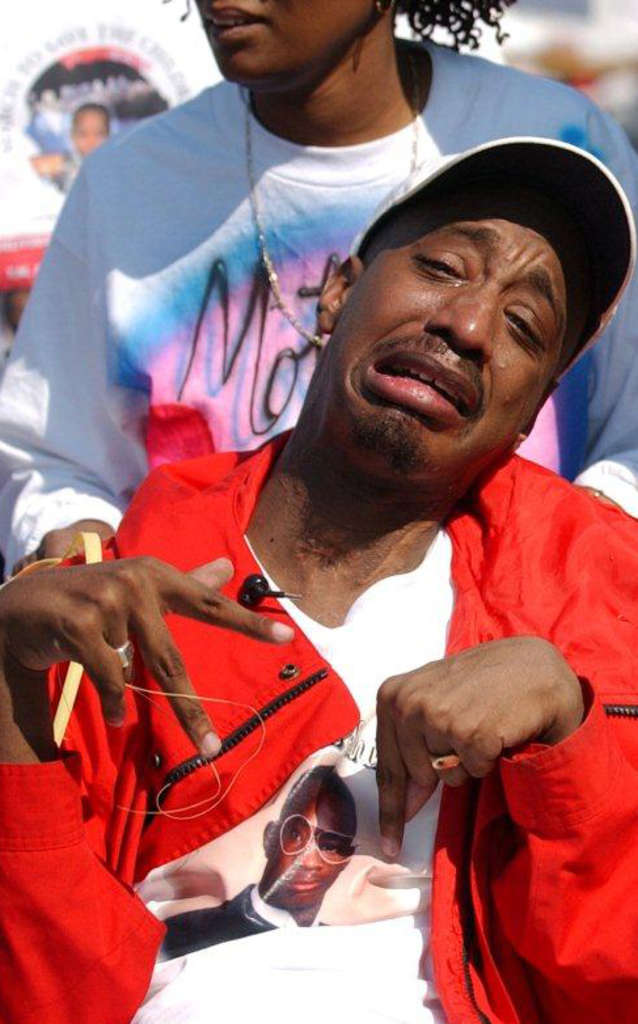

More than 100 people showed up for the birthday party at St. Joe’s Prep, family from all over the country and friends who had drifted apart after the shooting. Some hadn’t seen Smith in years. It was too painful, they said, to let reality replace their memories.

Some were shocked that he’d lived so long.

“He was supposed to be the guy who got out,” said Smith’s friend Pop Dixon, 45, of North Philly. “He was the brightest kid, the funniest dude I’ve ever met.”

Pictures of Smith, leaning on a red Lamborghini in a London showroom, hung on the walls. Guests signed a plastic version of the car with a marker. Everyone greeted Dee Pinkney with hugs and joined her on the dance floor.

“The bullet always wins,” said state Rep. W. Curtis Thomas, D-North Philadelphia, sitting by a window in the dining hall. “But if we had less guns and more mothers like Dee, it would be a start toward a better city.”

Beckett, the former teacher at St. Joe’s, was also among the guests. He said watching Pinkney care for her son for two decades only strengthened his own faith.

“Dee and Marcus paid the toll daily for the last 22 years,” he said. “Without seeking vengeance, without rancor, but with laserlike dedication and a heart full of love.”

The atmosphere at the party was festive, with colored balloons. They played funk, jazz, hip-hop. Nobody cried.

Dressed in white, Pinkney raised her hands toward the ceiling and sang with the crowd, celebrating the 22 impossible years her son had lived despite the bullet that nearly cut him down at 17.

“Happy birthday to you, Marcus,” his mother sang, inserting his name into the Stevie Wonder song.

But the young man who had dreamed of becoming a brain surgeon, a random victim of a stranger’s bullet, was only there in photographs.

Marcus Smith and his mother both wore white the previous day as she danced before his casket at St. Malachy, his body having given out, her rare and fragile flower finally plucked from the streets of North Philly.